In the process of painting, an artist will back away from a canvas and intentionally blur her vision, simulating distance, in an effort to take in the work as an aesthetic whole and not merely an accumulation of discrete marks, painstakingly applied. She may turn the canvas upside down, sideways, lay it flat to view from above, refreshing her vantage on the balance and rhythm of the overall composition. These “sensitivity tests” reflect an intuitive understanding that the work of art exists as a system, with a logic of color, form, and mark. Too tightly focused attention — fetishizing — on any one attribute of the work compromises overall system intelligence. Novelists allude to this call-and-response in writing when they answer the admiring reader’s query, “How did you write that character?,” by stating simply, “She wrote herself.” More medium than maker, an artist’s primary task is setting up conditions that invite, capture, and sustain system flow.

The speculative financialization of art — the last unregulated market — proceeds apace with the financialization of the global economy. However, distinct from the production of our built and natural world, we have yet to have financiers actually making the art, notwithstanding the entrepreneurial savvy of market players such as Koons and Hirst, themselves prefigured by Warhol, whose trenchant quip, “Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art,” speaks to his value-driver framework. Production systems of artist-led ateliers have been a mainstay since the Middle Ages, with themed templates and serialization maximizing output. Although responsive to patron dictates or cultural trends, an artwork’s value issues from the artist’s singular capacity to exceed base-line deliverables of verisimilitude (portraiture), reverence (religious art), and trophy ornament (something to hang over couch).

Bringing system intelligence to real estate

In the built environment, the real estate industry, comprising over a third of the world’s tangible wealth, has an especially counterproductive value-driver framework. This is interesting as the industry intersects two millennia-long sources of wealth creation — art and land. Financiers churning to keep ahead of real estate cycles deploy art and artists as cost-efficient value drivers, contributing cultural vitality to desultory, pro forma-driven, assembly-production developments. The land upon which these financial instruments are constructed, with their narrowly focused, fetishistic insistence on 18-month returns, is abstracted to a square-foot or per-acre line item. Yet, soil, according to geomorphologist David R. Montgomery, is the “delicate blanket of rotten rock that makes our terrestrial world habitable.” From an artist’s perspective, this profit maximizing delivery of our built world lacks system intelligence — socially and ecologically. By comparison, art produced to these crude, reductive metrics we call kitsch.

The status quo of real estate development not only squanders social and ecological capital, its brutal short-termism leaves unprecedented financial spoils on the table too. The Financial Times recently reported on one of the biggest intergenerational wealth transfers in history, an estimated $4 trillion in the U.K. and North America alone, anticipated in millennial inheritance from their baby boom elders. Millennial investment priorities: sustainability, clean energy, impact investing. Follow the money. “What is very clear to me is that millennials’ values are distinctively focused on making the world a better place, using financial capital for social return, having an impact and supporting sustainable development,” says Burkhard Varnholt, deputy global chief investment officer at Credit Suisse, in the FT. This newly wealthy generation, ready to start their own families, will choose to live and work in communities that align with these sustaining priorities.

Great art works are legacies, handed down generation to generation. Applying the artist’s holistic, system intelligence to producing the built environment is a legacy project, an investment that will perform financially, ecologically, and socially for generations to come. It requires a patron/investor/commissioning body to finance, an artist to envision, and her atelier of premier artists/artisans — designers, engineers, accountants, lawyers, contractors — to implement. This good business is the best art, for the earth and for each other.

The work of TILL

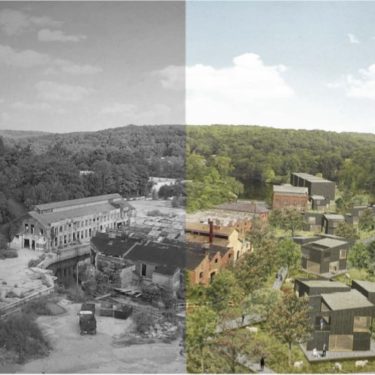

Upcycling downmarket suburbia through an aggressive three-part platform of decarbonization is the value driver framework of our community-based development practice, TILL. We target brownfields, industrially impacted landscapes, acquired at discount. Rather than remediate these damaged sites with conventional methods of encapsulation (“capping”) or “dig and haul,” we regenerate the soil using living plant material. Restoring soil health leverages soil’s capacity to sink carbon. Re-carbonizing the soil, decarbonizing the atmosphere: healthy soil deepens our carbon reservoirs. Brownfields comprise 20% of U.S. real estate, with the built environment contributing 1/3 of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. At scale, soil regeneration is a tool in our development portfolio to positively impact climate change, from the ground up.

Above ground, TILL builds new construction using cross-laminated timber (CLT), a jumbo plywood that is 50% sequestered carbon and a renewable resource. CLT construction is 30% faster and requires less heavy equipment than conventional construction, yielding cost savings while reducing the carbon footprint of building production.

Further decarbonization is realized in our mobility platform integrating AV, EV, dynamic ride and car sharing. Transportation contributes 27% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions; reducing private-car dependency with mobility options for mobility-poor suburbia is an economic catalyst that also offers critical social connectivity for aging populations as driving becomes untenable.

Like the iPhone, the world-changing, best-selling product of all time, TILL works because it aggregates decades-old, proven technologies of soil regeneration, mass timber construction, and smart mobility. Like the iPhone, TILL is confluence technology, not invention. Our innovation is the compilation and real-world implementation of these proven technologies for real-world impact that scales.

While our business strategy at project launch targets industrially impacted sites — buying value at discount — there is every reason to implement TILL’s confluence technology in urban and suburban sites beyond brownfield landscapes. Living in garden settings that contribute toward urgent decarbonization of our atmosphere aligns with the mission-oriented millennial and Gen Z age groups, prized as new business generators and a demographic canyon in aging ex-urban communities and disinvested municipalities.

Investment follows talent.

Talent pursues mission.

Mission makes market.

Anticipating both growing consumer demand for sustainable options and the inevitability of carbon pricing gives TILL competitive advantage and compounds future value as we build long-term community health and prosperity. This best art is excellent business.

TILL is an international, intergenerational, multidisciplinary practice focused on holistic community-based brownfield regeneration. It seeks community-specific solutions that engage the global context. TILL’s fiscal sponsor is the New York Foundation for the Arts.

Jane Philbrick is founder of TILL (Today’s Industrial Living Landscapes). Jane is graduate faculty in the Art, Media, and Technology Program at Parsons School of Design/The New School, NYC. She holds a bachelor’s degree from Barnard College, Columbia University, and a masters degree from the Graduate School of Design, Harvard University.

Olivia Greenspan, TILL co-founder, is a fellow at Fordham University’s Social Innovation Laboratory and is a junior at Fordham College at Rose Hill studying Economics.