By Diana Reynoso in a Fall 2018 essay for Rhetorikos.

Take a moment to picture New York City. Maybe the first thing that comes to mind is the iconic skyline—clustered structures of concrete, steel, limestone, and granite that pierce the clouds. Perhaps you envision Times Square—congested with thousands of New Yorkers and tourists, yellow taxi cabs and bike messengers, all immersed in a kaleidoscope of blinding lights. Or maybe you are thinking of Central Park—a green rectangle enclosed by a perimeter of buildings, sharply marking where nature ends and an urban oasis begins. While these are realistic visuals of the Big Apple, it would also be accurate to picture a foul-smelling cesspool with contaminated waterways and trash piling up on scorching-hot sidewalks. If action is not taken to tackle environmental stressors, such as stormwater runoff and the Urban Heat Island Effect, this repulsive reality of decay will instead become the primary visual people imagine when they picture NYC.

Like many other cities around the globe, New York City is a man-made environment designed specifically for Homo sapiens. From the moment Henry Hudson sailed to the shores of what the Lenape called Mannahatta in 1609, it would morph from a landscape that sustained diverse lifeforms into the human-oriented “Concrete Jungle” it is today. Dr. Eric Sanderson, an Ecologist at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and director of the Welikia Mannahatta Project, created an interactive map (pictured) that reconstructs what the city most likely looked like prior to urbanization (Sanderson 3). The city’s surface area has changed from a vibrant green to a dull gray, a contrast that never fails to alarm me. Nonetheless, urbanization gave birth to one of the most renowned cities in the world, one I proudly call home.

Unfortunately, the same process of urbanization that gave rise to such an iconic skyline has also led to serious problems. An outdated sewer system and a phenomenon known as the Urban Heat Island Effect are major environmental stressors endangering New Yorkers. These issues are by no means new to the city. In fact, ex-mayor Michael Bloomberg has been implementing PlaNYC initiatives since 2007, including the MillionTreesNYC project, aimed at addressing environmental problems in the city by planting trees on sidewalks. Even though some efforts have been made to improve the city’s health, they have not done much. The dangers posed by the city’s sewage system and the Urban Heat Island Effect demand a greater push to transform much of the city’s traditional, gray infrastructure into an innovative, green infrastructure. New initiatives should address these public health threats if we want to improve the quality of life for New Yorkers.

One of the most alarming environmental public health threats NYC is faced with has to do with stomach-churning sewage. Do you ever wonder what happens to your waste products when you flush the toilet? Well, if you live in an urban setting like New York, where almost two-thirds of the city relies on combined sewer systems, human waste and whatever else people flush down toilets ends up in sewers that “collect rainwater runoff, domestic sewage, and industrial wastewater in the same pipe” and is later transported to treatment plants before being discharged into designated bodies of water (EPA). On a sunny day, these systems are successful and hardly problematic. However, when it rains or when snow melts, water is diverted by impervious surfaces and runs off into nearby sewers. On a rainy day, H2O is not the only thing pouring onto the city. Raw, toxic, pathogen-infested sewage gushes out of these outdated sewer systems and flows into New York City’s streets and waterways. These are known as Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs), and the reason they happen has to do with the system’s design (pictured). Combined sewer systems let overflow occur when wastewater exceeds a capacity. This avoids overloading water treatment plants. City planners 150 years ago were not anticipating 8.5 million New Yorkers flushing their toilets into a shared network of pipes that overflow “when it rains a tenth of an inch per hour or more” (Chaisson). If a couple of hours of small-scale rain is enough to distress the system, imagine what a storm can do.

The Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn during a storm is an unfortunate example of the sheer failure of combined sewer systems. YouTube uploader “keanhokeanho” published a video on September 16, 2010 in which he documents raw sewage aggressively pouring into the Gowanus Canal. In the footage, one can see the turquoise color of the water disappear as it becomes consumed by a wave of gag-inducing garbage that carries “bacterial genera often associated with sewage impacted samples (e.g. Escherichia, Streptococcus, Clostridium, Trichococcus, Aeromonas) and…higher levels of Cu (copper), Pb (lead), and Cr (chromium) ”straight onto the doorsteps of local residents and even invades their homes (Deuker et al).

In response to events like these, New York State’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) hangs up signs reading “CAUTION” in bold yellow letters, advising New Yorkers to forget about their plans to go swimming, fishing, or paddling following wet weather events, disclosing that waterways “may contain bacteria that can cause illness.” CSOs are not limited to the Gowanus Canal. Jingyu Wang, a professor at the Bronx Community College, conducted a study that investigated the impact of CSOs on water quality in the Harlem River. The river was sampled for bacteria, ammonia, and other pollutants and found that “phosphate, ammonia, fecal coliform, E. Coli enterococcus levels increase during rainstorms,” which is a recipe for illness. You might be thinking that these issues are only relevant during heavy precipitation; however, this misses the point. Precipitation—whether it is light or heavy—is something we have no control over. What we can control is how we prepare our urban settings for naturally occurring events that are bound to happen. NYC needs to be designed in a way that can address the threat of stormwater runoff so New Yorkers are safe to indulge in and explore the city.

Another ailment the Big Apple is suffering from is a phenomenon known as the Urban Heat Island Effect. As the name suggests, an urban heat island is a metropolitan area that is significantly hotter than its surrounding suburban or rural areas. Joyce Klein Rosenthal, an EPA research fellow studying health and air quality, has discussed why this occurs in urban settings. She explains that urban heat islands are a result of “man-made surfaces, including concrete, dark roofs, asphalt lots and roads, which absorb most of the sunlight falling on them and reradiate that energy as heat” (Rosenthal). In turn, New York City is ten degrees hotter than its surrounding areas. This prompts New Yorkers to switch on their air conditioners to survive the sweltering summer months, resulting in increases in greenhouse emissions from power plants and higher energy bills.

Yet an expensive energy bill is not what is most frightening about the Urban Heat Island Effect. Heat-related deaths are a much more terrifying fate. Imagine being indoors on a scorching July afternoon in a hot apartment building that absorbs solar heat, as all buildings do. As drops of sweat accumulate around your forehead and begin to slide down your spine, you are faced with a tough call to make—an energy bill you cannot afford, or heatstroke. “On average, 447 patients each year were treated for heat illness and released from emergency departments, 152 were hospitalized, and 13 persons died from heat stroke,” a study assessing heat illnesses and deaths between 2000-2011 in NYC reports (Wheeler et al). The unfortunate reality is that many New Yorkers are at increased risk of heat-related mortality or heat illnesses, especially those with pre-existing conditions. In her book, Rosenthal evaluates the impacts of urban heat islands on public health and reveals that there are significant correlations between heat-mortality rates and low-income areas. These same areas have hotter surface temperatures and less access to air conditioning for elderly New Yorkers (Rosenthal 4). Although NYC provides air-conditioned spaces for those who qualify to use them, this option is only a temporary fix to a problem that will worsen the longer we keep a traditional, heat absorbing infrastructure. Unless action is taken to lessen the effects of urban heat islands, the concrete jungle is projected to get 2.5°F to 6.5°F hotter by the time we reach the 2050s, contributing to more heat-related deaths and illnesses (Knowlton et al).

To learn more about green infrastructure, I made a field trip to the WCS’s headquarters at the Bronx Zoo. There, I spoke to urban ecologist and educator Jason Aloisio, who has been studying green roofs for years. He describes the structure of a green roof as a “layer cake” and more complex than one would think (pictured). On the base layer is the roof, followed by an impervious surface, which is usually a rubber material that protects the roof from water. Next, we have a drainage layer shaped like an “egg carton” that allows water to move around. On top of that, there is a root barrier that prevents plant roots from penetrating the roof—which we certainly would not want. The next layer is a growing media layer and its purpose is to provide the plant with the nutrients it needs to grow while also absorbing water. This layer can have some soil, but it is usually made up of rocks and stones that allow water to evaporate. These materials are also heavier to resist the wrath of wind erosion. Last but not least, to top it all off like icing on a cake—the plants. Aloisio adds, “Green roofs could have slight variations to meet the needs of the roof it is on, but generally, this is how they are.”

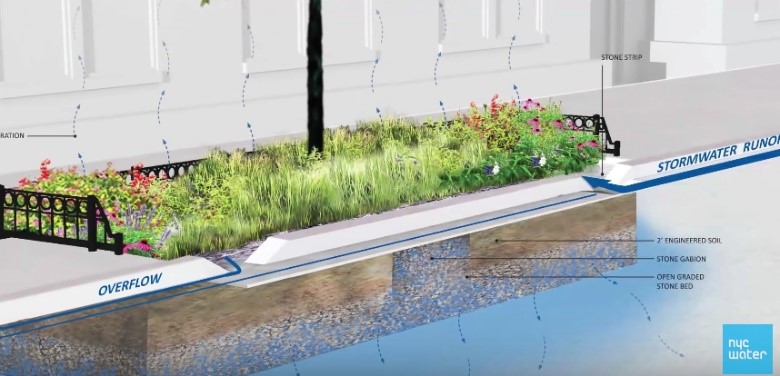

Another green infrastructure design gaining a lot of momentum are rain gardens, also known as bioswales. If you have taken a stroll in the city, you have more than likely come across trees in small, enclosed green spaces on sidewalks. These tree pits were brought in by Bloomberg’s MillionTreesNYC initiative and should not be mistaken for rain gardens. Bioswales (pictured) are engineered entirely differently. NYC’s DEP Green Infrastructure program is cultivating bioswales that feature layers of soil, broken stone, and carefully chosen vegetation to maximize the capture and treatment of stormwater during wet weather events. Bioswales are designed to catch water that falls from the sky and also have openings that guide runoff stormwater into them.

Still, how would green roofs and rain gardens mitigate the impacts of outdated sewer systems and the Urban Heat Island Effect? For starters, transforming traditional gray infrastructure into green spaces, both on roofs and sidewalks, would increase the surface area of green across the city and decrease impervious surfaces. This means there would be more surface area available to capture rain water and excess runoff water, preventing it from overloading sewer systems and stimulating a disaster. These green spaces encourage the natural movement of water via evapotranspiration, a process that evaporates water from soil, rocks, or stone, while plants use and release that water by ‘sweating’ through their leaves or stems during transpiration. Bioswales can generally hold more water than green roofs since the weight of accumulated water on a sidewalk does not pose any threats. In fact, NYC’s Department of Environmental Protection reported that thanks to its infiltration system of “engineered soil,” one bioswale alone can hold up to 45 bathtubs worth of water per rain storm and are designed to absorb all this water in less than 48 hours (NYCDEP). Reducing the amount of impervious surface area and replacing it with green also means there will be less surfaces to absorb heat from solar radiation. Instead, the plants on green roofs and bioswales will reflect and capture sunlight to conduct photosynthesis.

There are some green roofs already making a difference in the Concrete Jungle. The Javits Center’s bears a 6.75-acre green roof—the largest living roof in the city. Since its complete installation in October 2014, the venue has been enjoying countless practical benefits. In 2017, journalist Matt Alderton wrote an article about Successful Meetings, a magazine that allows department leaders to connect with the meeting-planning marketplace, and Succesful Meeting’s interview with Javits Center Senior Vice President Tony Sclafani. In the interview, Sclafani describes the green roof as a “modern-day miracle” because the roof has already absorbed 7 million gallons of stormwater; insulated the building in the winter and cooled it in the summer; and used 26% less energy than before. These results are from one roof alone. Imagine how much the city would benefit were these green spaces more widespread.

Green infrastructure not only mitigates the effects of stormwater and heat islands, but it also improves our quality of life. It is no secret that green spaces make us happier, and in turn promote our overall health. Multiple studies have supported a link between mental health benefits and green spaces. A study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health found that when there are higher levels of neighborhood green spaces, there were lower levels of symptoms associated with depression, anxiety, and stress (Beyer et al). This is especially important to low-income neighborhoods that have less access to green spaces and need to put in extra effort to reach them. These spaces are essential to healthy living and implementing greener infrastructure will make them more accessible. Ultimately, green spaces are only valuable if New Yorkers can reap their benefits.

In that same vein, it is easy to forget that New Yorkers are not just people. Urban wildlife will also need better access to green spaces for an improved quality of life. In the process of urbanization, cities have destroyed and displaced many animals. Fortunately, green infrastructure can help with habitat fragmentation and loss. In an NPR interview, Javits Center CEO Alan Steel reports, “We have 300,000 bees and we have seen 25 species of birds on the roof.” The Javits Center has even witnessed birds nesting on the roof (pictured). Many species in NYC live in unconnected green spaces, and a greater density of green infrastructure can help reconnect these green spaces to facilitate movement by serving as “stepping stones.” Imagine being a butterfly in Lower Manhattan trying to make your way through the hustle and bustle of the city to reach Central Park. There are very limited routes you could take and having more green spaces can make the task of pollination a lot easier.

The plethora of benefits these innovative solutions offer will make us wonder why they have not been widely implemented yet. Some are concerned that turning traditional infrastructure green will amount to great expenses. The EPA approximates that installing a green roof can range from $10 to $25 per square foot with under $1.50 per square foot in annual maintenance. The cost of installation may be an issue for some, but in one year the reduced energy consumption at the Javits Center translated into millions of dollars in savings (Alderton).

If cost is not the problem, then what is? Outreach specialist Emily Vail and shoreline conservationist Andrew Meyer were interested in figuring out potential barriers to adopting green infrastructure in the Hudson Valley. They surveyed people using open-ended questions regarding technical, legal, financial, and cultural barriers and found that respondents were most concerned about a lack of technical knowledge of or experience with green infrastructure, a lack of funding and incentives paired with perceived high costs, and a lack of legal structure for maintenance and ownership. Green infrastructure was also undervalued in Hudson Valley communities (Vail and Meyer 5). The results of this survey indicate that outreach is needed to inform communities and local governments about green infrastructure research and practices. Although this study took place north of New York City, it can shed light on possible concerns that serve as roadblocks to making the city greener.

Widely transforming the Big Apple’s gray infrastructure into green roofs and bioswales to address public health threats such as stormwater runoff and the Urban Heat Island Effect is a no-brainer. By 2050, 68% of the world’s population is expected to live in urban settings and it will be very important that our urban settings are carefully planned (United Nations). Cities like New York need to be equipped with the necessary infrastructure to sustain massive populations safely and provide a healthy quality of life. To ensure this, we will need more conversations and interdisciplinary work to occur between city planners, ecologists, policy makers, engineers, sociologists, and the public. Perhaps one day New York City’s iconic gray skyline will be known for being covered in green.

Works Cited

Alderton, Matt. “Javits Green Roof a Hit for Groups Meeting in NYC.” Successful Meetings, 24 July 2017, www.successfulmeetings.com.

Aloisio, Jason M. Personal interview. Dec 2018.

Beyer, Kirsten MM, et al. “Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental health: evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11.3 (2014): 3453-3472.

Chaisson, Clara. “When It Rains, It Pours Raw Sewage into New York City’s Waterways.” NRDC, 3 Dec. 2018, www.nrdc.org.

Department of Environmental Protection, NYC. Wastewater Treatment Process, www.nyc.gov/.

Dueker, M., G. D. O’Mullan, and R. Sahajpal. “Characterization of microbial and metal contamination in flooded New York City neighborhoods following Superstorm Sandy.” AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2013.

EPA. “What Are Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs)? | Urban Environmental Program in New England.” Environmental Protection Agency, 10 Apr. 2017, www.epa.gov.

Keanhokeanho. “9/16/2010: Storm Floods Gowanus Canal with Raw Sewage.” YouTube, 16 Sept. 2010, www.youtube.com/watch?v=HzWOOqPAEgs&t=44s.

Knowlton, Kim, et al. “Projecting heat-related mortality impacts under a changing climate in the New York City region.” American Journal of Public Health 97.11 (2007): 2028-2034.

Rosenthal, Joyce Klein. “Evaluating the impact of the urban heat island on public health: Spatial and social determinants of heat-related mortality in New York City.” PhD Dissertation, Columbia University, 2010.

Sanderson, Eric W., and Marianne Brown. “Mannahatta: An ecological first look at the Manhattan landscape prior to Henry Hudson.” Northeastern Naturalist (2007): 545-570.

United Nations. “68% Of the World Population Projected to Live in Urban Areas by 2050, Says UN.” United Nations, www.un.org.

Vail, Emily, and Andrew Meyer. “Barriers to Green Infrastructure in the Hudson Valley: An electronic survey of implementers.” Hudson River Estuary Program, NYS Water Resources Institute. Poster, 2012.

Wang, Jingyu. “Combined sewer overflows (CSOs) impact on water quality and environmental ecosystem in the Harlem River.” Journal of Environmental Protection 5.13 (2014): 1373.

Wheeler, Katherine, et al. “Heat illness and deaths—New York city, 2000–2011.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62.31 (2013): 617.